Jahangir Mohammed argues that Indian secularism and democracy have turned its Muslim minority into a persecuted underclass living in abject poverty.

India’s 200 million Muslims are its Hidden Underclass.

In 2023, India became the fifth leading economy in the world, overtaking Britain and France. It is a country with a huge population of 1.4 billion people of whom 80% are Hindus and 15% (around two hundred million) are Muslims. Yet behind the mask of a secular democracy, it is a deeply divided country with widespread discrimination and violence against large minority groups based on caste, faith, and sex, with extreme disparities of wealth.

India today is rabidly capitalist. Disparities of wealth are greater than that in the USA or Britain. The richest 1% of the population of India has monopolised 40.5% of the wealth created by the country between 2012-2021, according to a report by Oxfam. Only 3% of that wealth in that period trickled down to the bottom 50% of society. Yet 64% of taxes on goods and services came from this bottom 50%, while only 4% of these taxes came from the top 10%. India now has 166 billionaires some of whom support the BJP, with Gautam Adani becoming the richest man in the world. India’s 100 richest individuals had a combined wealth of $660bn in 2022, far greater than the wealth of many countries.

Caste, Discrimination and Poverty.

As well as capitalism, India’s caste system is another factor, responsible for discrimination, racism, oppression of women, and poverty. Even though the caste system is unlawful under the Indian constitution, it is endemic in Indian society. To understand discrimination and poverty in India an understanding of the caste system is necessary (see Appendix A at the end of this article).

In recognition of the impacts of casteism on lower castes and Dalits, Indian governments introduced policies of positive discrimination including quotas (called reservations) in government, employment, and education, for people from lower castes. Local governments classified people, communities, and castes to apply these policies. Lower castes were given the labels of Scheduled Castes (SC), and Scheduled Tribes (ST), and the slightly higher-ranked-but-still-poor were called Other Backward Classes (OBC). Those considered the original inhabitants of the land are known as Adivasis and classed ST (people who do not belong to a religion or are animists ). Some Muslim communities fall within the OBC category.

The population of Dalits (SC) is around 283 million, while 129 million are scheduled tribes (ST). The other backward class (OBC) constitutes around 47% of the population.

Although the situation has improved for many people in all these categories since 1947, and many have been lifted out of poverty, they remain the bulk of India’s poor. The Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2021, states that five out of six multidimensionally poor people in India live in households whose head is from an ST, an SC, or OBC.

The ST group is the poorest. Half of India’s tribal people, or 65 million out of a population of 129 million, live in multidimensional poverty. The estimate for SC or Dalits is 94 million out of a total population of 283 million.

Lawmakers have tried to address these realities of mass poverty and disadvantage by offering reservations. However, the BJP government is reviving old divisions using Hindutva ideology and a reinterpretation of Hinduism. It is attempting to change the policy of reservations by falsely claiming Muslims are the main beneficiaries of these policies. Although reservations on the grounds of religion are not allowed by most states, some Muslims classed as OBC have benefitted.

Muslims A Marginalised Community.

Dalits and lower castes have traditionally been seen as the main groups living in deprivation in India. However, discrimination and poverty among Muslims have received less attention. In 2016, a survey found that 25% of all beggars in India were Muslims while being only 14% of the population.

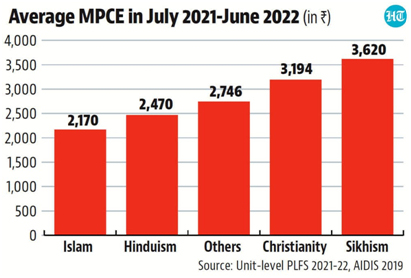

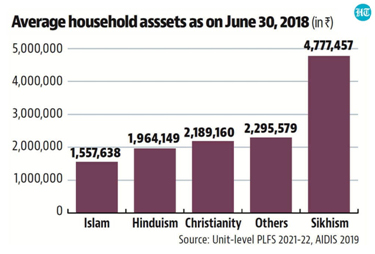

In June 2023 the Hindustan Times analysed the government’s All India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS) and Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). This highlighted that Muslims have the lowest asset and consumption levels of all religious groups in India.

The average Monthly Per Capita Consumption Expenditure (MPCE) for Muslims at 2170 rupees is lower than all other religious groups.

Muslims also have on average the lowest asset possession values compared to other religious groups at 1,557,638 rupees. This is also true for comparisons between classifications. Muslims in India are also divided by caste. Around 15% are those descended from upper castes, while 85% are descendants of lower castes who are now self-describing as Pasmanda Muslims. Upper-caste Muslims are poorer than even Hindu OBCs. The average asset value for non-SC/ST/OBC Muslims (i.e. not lower caste Muslims) at 1,563,953 rupees, is not just lower than the average value for non-SC/ST/OBC Hindus, but also lower than that of the Hindu OBCs category (1,841,523).

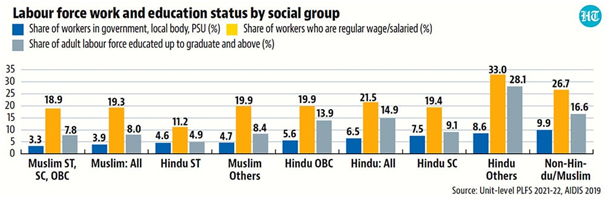

The Periodic Labour Force Survey data (PLFS) shows that the share of people with a graduate or higher degree among India’s Muslim labour force is the lowest among all major religions. It also highlights that even non-SC/ST/OBC Muslims have a low share in regular jobs (the average wage in such jobs is the highest) compared to other religions. The disadvantage for Muslims becomes even greater if one looks at their share in government jobs.

Education is vital to both job attainment and a route out of poverty. Free compulsory education is a right guaranteed in the Indian constitution. Yet in households in poverty children miss school to go and work to supplement family income. The literacy rate among Muslims is 57.3% and lags far behind the national average of 74.4%. That of Hindus is 63.6%, Christians 74.3%, Buddhists 71.8%, and Sikhs 67.5%. Muslims have the highest illiteracy rate of any single religious community in India.

Muslims also have the lowest enrolment rates in higher education than all other communities according to the All-India Survey on Higher Education Reports (AISHE) in 2018-2019. The percentage of Muslims in higher education was 5.2% for STs it was 5.5%, for SCs 14.9%, and OBCs 36.3%.

Political Representation and Oppression.

The political and legal repression of Muslims at the hands of the BJP and their Hindutva partners is now well documented. Muslims are subject to violence in the streets and villages, sometimes leading to lynchings to death. Muslim homes and mosques are sometimes bulldozed or targeted by the state. Over 2,900 cases of communal or religious rioting were registered in the country between 2017 and 2021, Muslims suffer most from sectarian rioting and violence, and when they report matters to the police it is less likely that action will be taken against perpetrators. Since 2014, there has been a raft of anti-Muslim laws introduced by the BJP (or regional states under their control) that have led to further repression of Muslims.

The persecution of Muslims has impacted their confidence to seek education, get jobs, and do business outside of Muslim areas, which in turn further entrenches poverty in that community.

What of Muslim political representation and activity to be able to challenge oppressive policies of governments?

The situation in terms of political representation, although not on its own a marker of political power and influence, is telling. In 2019, twenty-seven or just under 5% of Muslims were elected to the 542-seat Lok Sabha. This compares to 4.3% in the first election in 1952 and its highest of 9.3% in 1977. There is currently no Muslim legislator in the current ruling government for the first time in India’s history.

While the BJP has fielded one Muslim candidate in the ongoing general elections, and its ally JD(U) one more in Bihar, among the key opposition parties too Muslim selection has fallen. The Congress, Trinamool Congress, Samajwadi Party, RJD, NCP, and CPI(M) have fielded 78 Muslim candidates this time, down from 115 in 2019.

The political representation of Muslims at the state level is only slightly better. India has more than 4,000 lawmakers in state legislatures across twenty-eight states and Muslim lawmakers number 6% (around 240 of these seats).

If we compare this with the UK there are 21 Muslims (11 women) in the 650-seat Parliament or 3.2% of a 4 million or 6.5% population.

More Persecution and Marginalisation Post 2024.

Another victory for the BJP in the current election will lead to the further consolidation of the RSS Hindutva project. This seeks to reduce Muslims to a subjugated community living under the domination of the Hindu majority, rather than as equal citizens. There has been talk of altering the constitution to reflect Hindu law (Manusmriti) and the introduction of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) on family law which will replace diversity and impact Muslims. Some BJP-controlled states such as Telangana have also committed to ending reservations for Muslims that were introduced by Congress to tackle deprivation.

Muslims in India are not just a huge minority of two hundred million. They are the third biggest population of Muslims in the world after Indonesia and Pakistan. There are many lessons to be learned from India for all Muslim minorities everywhere. We will address them in the future. The central one to come out of India is that democracy and secularism alone can never be a guarantee of security for minorities. The future does not look bright for India’s Muslims. Yet they will have to find a way to deal with their political and economic repression.

Appendix A. Outline of Caste System

The caste system is the world’s oldest surviving form of social stratification. Varna is a Sanskrit word that can be translated as ‘class’. It is a division of society with origins in the Vedas (the oldest texts of Hinduism). Many Hindus believe class originates from the Hindu God of creation, Brahma. The purpose of the varna system was to distribute responsibilities among the people. It is argued that a healthy, prosperous, and strong society can only exist if the caste system is maintained. India’s caste system classifies Hindus into four varnas (classes) based on their occupation:

- A Brahmin is a member of the highest caste or varna and is an incarnation of knowledge (priests and teachers)

- The Kshatriyas are the second highest of the four varnas representing warriors, aristocracy, aristocracy, and rulers.

- Vaishyas (farmers, traders, merchants i.e. businesspeople) are the third class of the caste system.

- Sudras (labourers) are the lowest of the four classes of the caste system.

Jati is from the Sanskrit root Jaha meaning to be born. Each of the four varnas contains many Jati’s (around 3000). A Jati describes a group or community that has generic hereditary characteristics and requires endogamy (marriage within the same group). A person’s Jati determined his/her occupation and status, and those with whom he/she was permitted to eat and drink, to interact socially, and to marry. Each Jati has its own rituals and customs.

Leave a Reply