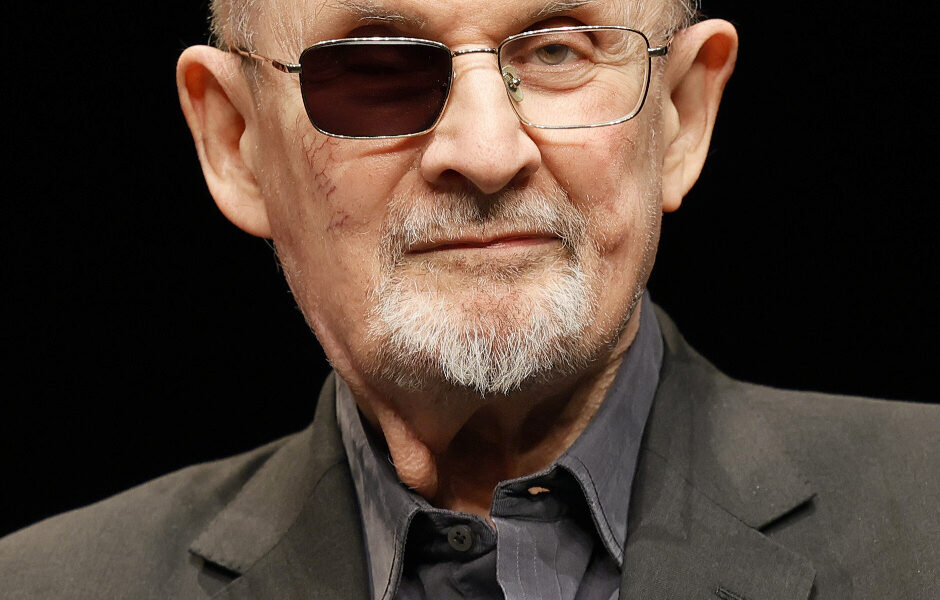

Jahangir Mohammed argues that Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses”, published in 1988, was the spark that lit the fire of Islamophobia in the UK, and uses AI to assess his argument.

Salman Rushdie: The Author And Populariser of Contemporary Islamophobia.

Today, Islamophobia, its form, propagation and proponents are widely understood by Muslims and many non-Muslims alike. Muslims are also aware of the tactics of some ex-Muslims and other individuals who find attacking/writing about Islam presents an opportunity for fame and fortune. They may have left Islam, but they seldom leave Islam alone.

Yet in September 1988, when Viking Penguin (Penguin Books) published “The Satanic Verses”, very few Muslims understood Islamophobia. The term had not been invented in the UK. Salman Rushdie, an atheist brought up in an Indian Muslim family, had modest success as an author by selling Indian culture/history to non-Muslim audiences. His first successful novel was “Midnight’s Children”. For this, he was paid the paltry sum of $7,500 in advance. His next novel was “Shame”, which did not get as much traction. On the back of these novels, Rushdie became well known. He also became a darling of the mainly liberal race relations industry, which was concerned with racial inequalities and promoted multiculturalism. It seems to me his novels appealed because they had some cultural content sprinkled with Western tropes and stereotypes about Indians/Muslims, which reinforced notions of Western civilisational/cultural supremacy. Much of the British establishment held such views, as did many in the race relations industry. I found his novels unreadable and boring myself.

For the Satanic Verses, Rushdie was reportedly paid $850,000 in advance (a considerable amount in 1988). Penguin were expecting big sales and a return on their investment. Writing polemics against Muslims/Islam for traction was about to take off in the West and through an ex-Muslim.

The Muslim Awakening

In September 1988, Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses” was published. The content and target was Islam and Muslims. It was always going to be controversial and explosive and cause great offence and hurt to Muslims worldwide. As an Indian brought up in India in a Muslim household, Rushdie must have known this.

Up to that point in UK history, Muslims were not viewed through the lens of Muslim identity and were seen as Asians, Black or dealt with through their ethnic identity. Most even self-identified as such. The big issue in race relations was racism, not discrimination and prejudice on the grounds of religion, which was not even covered under the Race Relations Act.[i]

For most Muslims, this was the beginning of an awakening or realisation that racism and the race relations laws/industry were not equipped to deal with hatred and discrimination based on the Islamic faith. The Muslim community also realised that by being part of anti-racism campaigns (although necessary) and submerged in the race relations industry and party politics, whilst not speaking about their faith and relegating it to the background, had only served to leave deep-seated historical hatred of Isam and Muslims unexposed and unchallenged. The book awakened a consciousness of Muslim identity.

The politics and community activism surrounding the Rushdie Affair was a journey of mutual self-discovery (a boxing match and power struggle) between the Muslim community and the establishment. Each party discovered more about the other. The Muslim community were lectured about the need for freedom of expression, the West’s values, not burning books and the need for integration. The Muslim community, which had not previously tried to articulate its politics, responded by referring to the pain and hurt that they felt and pointed to Christianity being protected through the blasphemy laws and freedom of speech not being absolute.

The book’s publication led to many events, including protests, book burning, attempts at legal action and a fatwa. Both sides learned a great deal about each other. The Muslim community had communicated its red lines to wider society whilst learning about the Western establishment’s hatred of Islam. The Muslim community also realised that party politics and a race-based industry were not sufficient to pursue Muslim political interests, and they needed to develop independent political organisations.

The Beginning of Contemporary Islamophobia

The Satanic Verses not only turned Salman Rushdie into a global household name but also an icon for free speech for the West as well as a reviled figure in the Muslim world. I had read the Satanic Verses at the time. For a Muslim, the offensive, insulting narrative with Punjabi swearwords thrown in for fun is a challenging read without getting angry.

I have always seen the book and its content through the lens of prejudice, stereotyping, and hatred, not a novel, freedom of expression, or the UK concept of blasphemy. I was already familiar with Christian and Oriental European history of anti-Islamic narratives and propaganda. I had been given a book by an author on the topic long before. I recognised those narratives in the book. Today, people hear those tropes and stereotypes regularly but may not see the link with the Satanic Verses.

My conclusion many years ago was that Salman Rushdie and the Satanic Verses popularised the narratives of contemporary anti-Islam and anti-Muslim propaganda and hate. I had said as much to a radio programme on the Rushdie affair a few years ago (not that they would publish that part).

For me, the confirmation of this is that far-right and nationalist groups and politicians started to adopt the narratives outlined in his book into their politics, and those views are now widely articulated in the media and British politics.

More recent confirmation comes from India, where the Satanic Verses had been banned for publication and sale. The ban was lifted last year in a political climate of the rise of Hindutva nationalism in India, which is now a hotbed for Muslim hate. Many of the tropes and narratives in the book are mainstream in India.

However, I have always wanted to analyse the book again to chart the Islamophobic stereotypes and narratives to see how far my assessment is correct. However, I did not want to read the book again and felt that anything I produced might be biased. Thankfully, with the aid of Artificial Intelligence, I no longer needed to interrogate it. I decided to use AI. Those interested in the results of AI assessment of the anti-Islamic tropes and narrative in The Satanic Verses can read them below. They make for interesting reading and confirm for me that the Satanic Verses was the spark that lit the fire of Islamophobia in the UK.

A warning: Muslims may find the analysis of the book’s content below highly offensive.

[i] In fact, despite campaigns by the Muslim community, religion did not become a protected characteristic until the UK incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights into the Human Rights Act of 1998.

- IDENTIFY VARIOUS TROPES AND STEREOTYPES ABOUT ISLAM AND MUSLIMS IN THE SATANIC VERSES BY SALMAN RUSHDIE.

- The Prophet Figure (Mahound)

- Tropes: The depiction of the Prophet Muhammad as “Mahound” plays into colonial and Orientalist stereotypes of the prophet. Mahound is a name historically used by Christian polemicists to demonize the Prophet Muhammad, suggesting a false or demonic prophet.

- Criticism: This portrayal can be seen as part of the trope of the “imposter prophet,” a stereotype seen in medieval Christian depictions of Islam. By naming the character Mahound, Rushdie invokes this negative historical stereotype.

- The Satanic Verses Incident

- Tropes: The novel fictionalises the Qur’anic story of the “Satanic Verses,” in which the Prophet is said to have briefly mistaken Satan’s words for divine revelation before retracting them. This incident is controversial in Islamic history and is generally considered fabricated by Islamic scholars. The novel uses this event to explore themes of doubt and faith.

- Criticism: The use of this narrative element reinforces the stereotype of Islam as a religion rooted in ambiguity, error, or deception.

- The Portrayal of Women

- Tropes: The novel includes multiple instances of Muslim women being portrayed in hyper-sexualized or subjugated roles. For example, the depiction of the brothel in the chapter “Return to Jahilia,” where the prostitutes assume the names of the Prophet’s wives, plays into the stereotype of the oppressed and eroticised Muslim woman.

- Criticism: These representations align with Orientalist depictions of Muslim women as either victims of a patriarchal system or objects of sexual fantasy, reinforcing Western stereotypes about gender roles in Islam.

- Islam as Intolerant and Backward

- Tropes: In the novel, there are moments where Islam is depicted as rigid, intolerant, and opposed to modernity. Mahound’s city of Jahilia represents a pre-Islamic era, but his arrival brings a stark, authoritarian religiosity.

- Criticism: This reflects a common Western stereotype of Islam as fundamentally intolerant or resistant to progress, a depiction that plays into postcolonial ideas of the “clash of civilisations.”

- Blasphemy and Apostasy

- Tropes: The novel explores the theme of apostasy, particularly through the character of Gibreel Farishta, who questions his faith and even plays a blasphemous role as the Archangel Gabriel. Islam is portrayed as a faith intolerant of doubt or criticism.

- Criticism: The stereotype that Islam suppresses intellectual and spiritual freedom is present in this narrative. Characters who question or leave Islam are depicted as facing severe repercussions, which reflects common Western critiques of Islam as intolerant of dissent.

- The Indian-Muslim Immigrant Experience

- Tropes: The novel’s protagonists, Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha, are Indian expatriates who struggle with identity and faith in the context of migration to the UK. Their experiences reflect broader questions about the Muslim diaspora, particularly around assimilation and cultural identity.

- Criticism: At times, their disillusionment and rejection of Islamic identity can be seen as reinforcing the stereotype that Muslims, especially immigrants, must either fully assimilate into Western norms or remain trapped in backwardness.

- Violent Fanaticism

- Tropes: The novel also plays into the stereotype of Muslim fanaticism, especially through the character of the Imam, a figure reminiscent of Ayatollah Khomeini. This character is depicted as a zealot who uses religion to justify authoritarianism and violence.

- Criticism: This is a reflection of the common Western trope that positions Islam as a religion prone to extremism, and it reinforces the image of Muslims as being easily radicalised.

- The Theme of Mimicry and Cultural Conflict

- Tropes: Saladin Chamcha, one of the protagonists, represents the idea of mimicry, trying to completely assimilate into British culture and rejecting his Muslim and Indian heritage. This plays into the trope of the Muslim or colonial subject trying to shed their “inferior” culture in favour of a “superior” Western identity.

- Criticism: The portrayal can be interpreted as reinforcing the stereotype of cultural inferiority, where the Muslim migrant’s identity is only validated by how well they assimilate into the West.

- The Miracle-Performing Saint (Ayesha)

- Tropes: The character of Ayesha, a mystic who leads a group of villagers on a pilgrimage to Mecca, evokes the trope of religious fanaticism and superstition. Her conviction that the Arabian Sea will part for them during their journey is portrayed as irrational and tragic.

- Criticism: This plays into the stereotype of Islam as a religion rooted in superstition, where blind faith leads to self-destruction.

- Postcolonial Islam and Power

- Tropes: The novel explores how Islam is entangled with issues of colonialism and postcolonial identity, particularly in India and the UK. However, some critics argue that Rushdie’s depiction of Islam focuses on its oppressive potential and its complicity in authoritarianism.

- Criticism: By focusing on the authoritarian aspects of Islam in postcolonial contexts, Rushdie is accused of playing into Western fears about Islam’s role in global politics and its perceived threat to democracy and freedom.

- WHICH RELIGIOUS PRACTICE DID SALMAN RUSHDIE CRITICISE IN THE SATANIC VERSES

- Blind Obedience to Religious Authority

- Critique: Rushdie repeatedly questions the tendency of followers to adhere blindly to religious leaders and figures. This is most apparent in the novel’s depiction of Mahound, the fictionalized version of the Prophet Muhammad, and his control over his followers. The portrayal suggests a critique of the absolute authority that religious leaders wield over their communities, particularly in shaping moral and political life.

- Example: In the city of Jahilia (a stand-in for Mecca), Mahound’s rise to power brings with it a system of religious rules that are strictly enforced, questioning the interplay between religious authority and personal freedom.

- The Concept of Revelation

- Critique: Rushdie critiques the notion of divine revelation, particularly the idea that it can be influenced by worldly forces. In the novel, the “Satanic Verses” incident refers to a moment where Mahound (the Prophet Muhammad’s character) is depicted as being misled by Satan into speaking false revelations, which he later retracts. This reflects Rushdie’s exploration of the fallibility of religious leaders and the human element in what is often considered divine.

- Example: The “Satanic Verses” incident questions the concept of absolute truth in religion, suggesting that even the divine message can be subject to human error, manipulation, or political interests.

- Fanaticism and Extremism

- Critique: The novel explores how religious fervor can easily turn into fanaticism, particularly when it is used for political ends. Through the character of The Imam, who is a stand-in for modern theocratic rulers like Ayatollah Khomeini, Rushdie critiques the way religion can be weaponized to justify authoritarianism and violence.

- Example: The Imam is portrayed as an extremist religious leader in exile, using religion to consolidate political power and enforce strict religious laws on society, all while suppressing dissent and individual freedom.

- The Subjugation of Women

- Critique: Rushdie critiques the treatment of women in religious systems, particularly the way they are often oppressed and their roles defined solely by patriarchal religious structures. This critique is most explicit in the scenes involving the wives of Mahound and the brothel scene, where prostitutes take on the names of the Prophet’s wives.

- Example: The scene is a pointed critique of the idealization and control of women in Islamic society. By juxtaposing the Prophet’s wives with sex workers, Rushdie highlights the way religion can simultaneously exalt and confine women to predefined, often subservient roles.

- Religious Pilgrimage and Superstition

- Critique: Through the character of Ayesha, who leads a group of followers on a pilgrimage believing that the Arabian Sea will part for them, Rushdie critiques the dangers of blind faith and religious superstition. Ayesha represents a form of extreme religious devotion that leads to tragic consequences.

- Example: Ayesha’s unwavering belief in a miracle during the pilgrimage, despite the eventual drowning of her followers, critiques how extreme devotion can lead to disastrous outcomes when people place faith in the miraculous over the rational.

- The Use of Religion for Political Control

- Critique: Rushdie critiques the way religion is often intertwined with political power, suggesting that religious leaders and systems use faith as a tool to control populations and suppress freedom. The novel frequently addresses how religion, particularly Islam in this case, can be exploited to establish authority and justify political dominance.

- Example: Mahound’s ascent to power is shown as being rooted not only in religious preaching but also in consolidating political power. The narrative suggests that religious dogma is often used to justify the subjugation of dissenters and the enforcement of societal control.

- Apostasy and Blasphemy

- Critique: The novel questions the severe penalties for apostasy (leaving the faith) and blasphemy (criticism or defamation of religious beliefs). Through characters like Gibreel Farishta, who struggles with his faith, Rushdie explores the idea that individuals should have the freedom to question, criticize, and even abandon their religion without facing persecution.

- Example: The novel itself was seen as blasphemous by many Muslims, and the controversy surrounding it highlighted the very issue Rushdie was critiquing—the harsh societal and sometimes violent consequences of perceived blasphemy and questioning of faith.

Leave a Reply