Jahangir Mohammed argues that the Kidnapping of President Nicolas Maduro and the theft of Venezuelan resources by Gringo loco (Crazy American) Donald Trump will be seen as another chapter of a 500-year colonial history of a race and class caste system and struggle that will lead to more resistance against US imperialism in Latin America.

The 500-Year-Old Race and Class War at the Heart of the U.S. Abduction of Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro

It was a day in history which shocked the world, the kidnapping of the Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife by US forces from their homes and taken to the US.

In Washington, this attempt at regime change is framed as authoritarianism against democracy, a human rights issue, tackling crime and regional security. However, Donald Trump and other US leaders have explicitly stated that it is about seizing the country’s oil resources. Other commentators point to Venezuela’s pro-Palestine stance and the pursuit by the US of a pro-Israel agenda.

But behind the attempted regime change and theft of resources lies a deeper fracture within Venezuelan and Latin American societies and in their relationship with the US empire. When viewed through this older lens, the politics and struggles of the Venezuelan and Latin American people become clearer.

The US military intervention and oil theft is simply the latest chapter in a centuries-old struggle between a light-skinned (white), European-origin, Western-aligned elite and a mixed-race majority nationalist pueblo (an oppressed, poorer class majority seeking to reclaim their identity, heritage and equality). To understand why Venezuela’s crisis is so intractable and why US policy resonates with some (or backfires) as it does, we must look beyond economics and geopolitics to the deep-seated social architecture of Latin America.

Venezuela’s Colonial Caste System

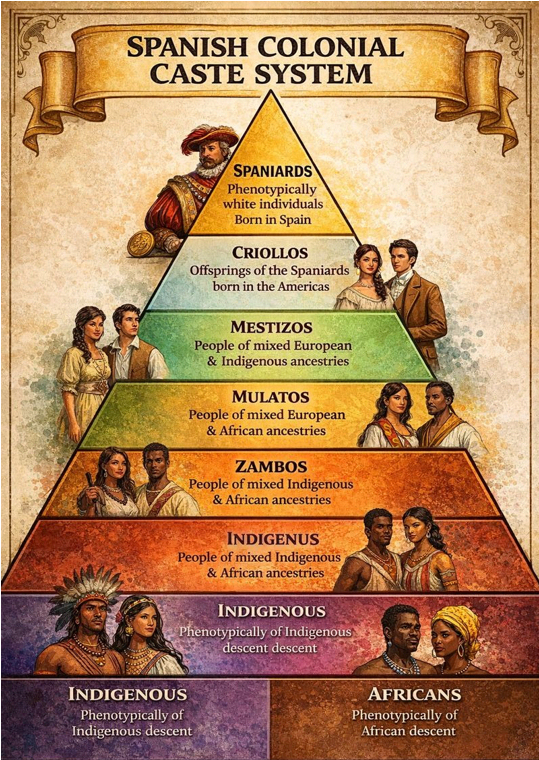

Venezuela’s current chasm is not a product of 21st-century socialism. Its foundations were laid in 1522, with the first Spanish settlements. The Spanish colonial caste system established a rigid hierarchy: peninsulares (whites born in Spain) at the top, followed by criollos (offspring of Spaniards born in the Americas), and then descending through gradients of mestizo (mixed-race), indigenous, and African slave ancestry. After independence, the criollo landowning class inherited power. For nearly 500 years, political control, economic wealth, and social prestige in Venezuela were overwhelmingly concentrated in the hands of a light-skinned minority. This elite modelled its culture, education, and aspirations on Europe and, later, the United States. Their children studied at US universities, their capital was tied to joint oil ventures, and their political vision was of a Venezuela integrated into the Western liberal order.

This created a nation marked by a profound psychological and racial divide. Over half the population is mestizo (50.6%), with significant Afro-Venezuelan (Pardos 4.6%) and indigenous minorities. Yet the faces of power in business, media, and politics remained predominantly white (the Blanco population is 43.6%).

By the mid-20th century, under the Puntofijo party-pact democracy (a pact between the two main political parties that managed the racial divide but never healed it), a professional political class, still largely light-skinned, educated, and pro-Washington, administered the state. While oil wealth fuelled a middle class, the poor, predominantly non-white majority remained structurally marginalised, and their culture and heritage were sidelined by the official narrative of progress. Colour determined class, and class, in turn, determined one’s life, as it had under the Spanish colonial caste system.

The Chavez Revolution

The Chavez Revolution

Then came Hugo Chávez in 1998. A mestizo former army officer from the rural plains, of obvious indigenous and African descent, Chávez did not merely propose new policies; he launched a cultural and racial revolution (the Bolivarian Revolution). He was in effect the first mestizo leader of Venezuela.

His rhetoric explicitly appealed to invert the old hierarchy. He championed the “pardocracia”, the rule of the mixed-race masses, against the “oligarquía” and “escualidos” (the squalid ones), terms with unmistakable racial and class connotations. He reframed history, venerating indigenous and Afro-Venezuelan figures while portraying the pre-1999 republic as a kleptocratic project of the elite. His foreign policy was a defiant pivot away from the US “empire” towards a Global South axis. He was also the first to identify the Palestinian people’s struggle with that of the oppressed in his own country’s struggle against US imperialism.

Chávez’s project was the most successful political mobilisation of Venezuela’s non-white and poor majority in its history. It was not merely a shift in ideology but a long-delayed assertion of national identity and sovereignty by the demographic majority. For the traditional elite and a terrified middle class, fearful of losing their wealth and privileges, it was perceived as an authoritarian, economically illiterate takeover that would destroy the country. As usually happens in a revolutionary change the previous ruling elite and those who benefitted from it and those middle classes with wealth tend to leave and become exiles to preserve their wealth. They then become a diaspora in opposition. The stage was set for a conflict in which every political dispute over the economy, the media, and foreign policy was filtered through this historical divide of race, class, and grievance.

Enter the United States. Washington’s consistent opposition to Chavismo, with harsh sanctions and crippling its main source of income oil, culminating in its leading the West in recognising opposition leader Juan Guaidó (from the traditional white elite) as interim president in 2019 (from the traditional light-skinned elite). This was interpreted in Venezuela through this existing racial and class lens. For the Chavista base, US policy was not neutral intervention but the inevitable return of the oligarchy’s old partner, aimed at restoring the old order. Every sanction was seen as proof of an imperialist attack on the nation’s sovereignty and on the poor who depended on the state. For the opposition, US support was a necessary lifeline against a “tyrannical regime” that had destroyed democracy and aligned with global adversaries.

This dynamic explains the paradox of Venezuela’s opposition: figures such as the currently banned candidate Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Corina Machado, a light skinned industrial engineer of Portuguese and Spanish descent, educated at elite institutions, pro-Israel, and championed by Western capitals. To her supporters, she embodies competence, democracy, and a return to the global community. To the government and its base, she is the living avatar of the reviled oligarquía, a symbol of the world that used to be and that seeks to return. US endorsement of her reinforces this centuries-old narrative in the minds of Chavistas, making a purely electoral solution nearly impossible, as the contest is not just about programmes but about national identity itself.

White elites in the exiled Venezuela diaspora community and the wealthy middle classes in the US have been seeking a return to the old race and class order. For the US administration under Trump, they co-opted politicians who shared their white supremacist worldview and who were willing to act to help remove Maduro.

Latin American Shared Pattern, Different Outcomes

Venezuela’s story is an acute, heightened version of a pattern found across the continent. The colonial template of a white/mestizo elite governing over a mixed-race, indigenous, and African-descendant populace is Latin America’s original sin.

In the Andean nations of Peru and Ecuador, politics have long been marked by tensions between the white-mestizo coastal elites of capitals like Lima and Guayaquil and the large, impoverished indigenous populations of the highlands. Like Chávez, leaders like Peru’s Pedro Castillo (a rural teacher of indigenous descent) have ridden this divide to power, channelling deep-seated resentment against the traditional ruling class.

Bolivia offers the clearest parallel and contrast. Like Venezuela, it elected a transformative, indigenous president, Evo Morales, who explicitly overturned the political dominance of the light-skinned elite of the eastern lowlands. The subsequent conflict was intense, involving accusations of US meddling. However, Bolivia’s political settlement has, so far, proven more resilient than Venezuela’s, in part because Morales’s movement was more institutionally rooted in powerful social organizations.

Brazil and Argentina present different demographics but similar elite structures. Brazil’s powerful agribusiness and financial elites are overwhelmingly white and maintain deep ties to Europe and the US, while its political landscape has been shaped by the tension between this group and the populism of the Workers’ Party, which drew power from the non-white poor in the urban peripheries.

Argentina presents a contrasting model. While Venezuela’s conflict arises from a majority mestizo population overthrowing a minority elite, Argentina’s social tensions unfold within a nation that consciously made itself one of the whitest in the region through calculated demographic engineering effectively creating a “white republic”.

In the late 19th century, Argentina’s liberal elite, viewing their mixed-race population as an obstacle to modernity, embarked on a radical project: “Gobernar es poblar” (“to govern is to populate”). They actively recruited millions of immigrants from Italy and Spain, while simultaneously waging the “Conquest of the Desert” to exterminate Indigenous populations on the Pampas. The result was a demographic transformation. Today, 85-90% of Argentines identify as of White European descent, a stark contrast to Venezuela’s mestizo majority.

This engineered demography changed the nature of political conflict. Argentina’s fierce struggles are between Peronist populism and liberal elitism, not racial. The divides are ideological and economic, expressed through the lens of class and political tribalism. When the US engages Argentina, it engages a nation whose core identity is fundamentally European; the existential, racialised dimension of “the other” that fuels Chavismo is largely absent. This explains why Argentina is the most pro-Western and Israel loving country in Latin America. It is no surprise that Argentina’s President Javier Milei celebrated the US action against Maduro.

Mexico underwent its seismic racial-class confrontation a century ago with the 1910 Revolution, which violently dismantled the Porfirian elite and enshrined mestizaje (racial mixing) and social justice in the state’s policies, even if inequality persists.

The critical difference between other Latin American countries and Venezuela is that the confrontation did not become so perfectly geopolitically aligned. Venezuela’s blessing was its vast oil wealth, making it a strategic curse and prize for the US. The charismatic, nature of Chávez, who made anti-American imperialism a cornerstone of his ideology was bound to lead to a conflict. This turned an internal social conflict into a proxy battleground in a renewed Cold War-style struggle, with Russia, China, Iran, and Cuba backing the revolutionary state, and the US, Canada, and the EU backing the opposition to him from the old elite.

The Stalemate and the Path Forward

President Maduro is incarcerated as a hostage of the US, and Venezuela is under an imperialist economic siege. Its economy was already shattered by sanctions. Donald Trump is demanding its leader’s hand over oil and contracts and cut relations with Iran and China. Even suggesting that Gringo loco (eccentric or wild foreigner from the US) could rule Venezuela himself. However, the revolutionary government has not yet been overthrown, and Vice President Delcy Rodriguez (a mestiza) remains in position if she can cut a deal with Trump and the US. Donald Trump’s advisers may have realised that the white Maria Machado is unlikely to be accepted by the majority mestizo Venezuelans and that the Bolivarian revolution has been too deeply embedded in the people to be overthrown militarily. An easier option is to cripple it and bully it into compliance and change.

However, a long-term solution for Venezuela, must grapple with this foundational schism. It requires more than power-sharing agreements between politicians, or externally imposed theft of resources. it requires a reconciliation of national narratives. It will require opposition, and its international backers, to genuinely acknowledge and address the historical exclusion that gave birth to Chavismo, moving beyond a simple “restoration” of the pre-1999 order. The US, the imperialism and political order it seeks to impose by force and bullying is unlikely to resolve the underlying issues but mainly inflame them.

Conclusion

For the United States and the wider international community, the lesson is that policies which are perceived as taking a side in Latin America’s internal schism will inevitably fuel more resistance and radicalisation. Support for democracy does not equate support for a specific social class and elite or parts of a diaspora community that aids an imperialist agenda. Engaging with the complex reality of Latin American societies means understanding that for millions, the figure of a light skinned (white) US educated opposition leader is not a symbol of hope, but a spectre of a past they have spent decades fighting to overcome.

The United States today, in seeking regime re-direction and kidnapping Maduro, is not just intervening in a foreign policy dispute or removing a “dictator”, it is stepping on a battlefield that the white supremacists running the US cannot comprehend or win. It is intervening, with all the weight of its history in the hemisphere, in a 500-year-old social conflict. Every sanction and every endorsement is filtered through a powerful historical narrative of race and class war. Until US strategy accounts for this profound reality, moving beyond seeing Venezuela purely through the lenses of geopolitics, liberal democracy and oil its policies will continue to achieve tactical pressure at the cost of strategic failure. The path forward requires a humility and a historical awareness that have so far been in short supply. The goal is not to choose a side in Venezuela’s caste and class war, but to create conditions where Venezuelans themselves can finally move beyond it. Only the Venezuelans themselves can do that.

Leave a Reply