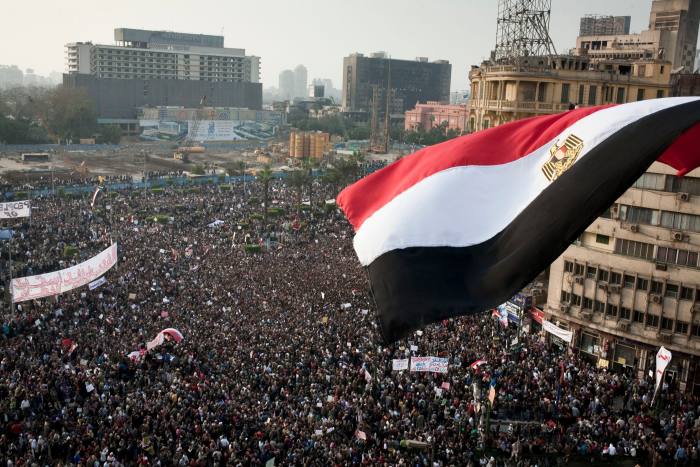

10 years ago, on the 25 January 2011, a wave of mass protests started in Egypt, following on from those in Tunisia ( which started the previous year). These popular mobilisations of people across different Arab countries are now being widely referred to as revolutions in the media. However, did these protests, and what came afterwards, achieve what is known as a revolution ? In short, the answer is no.

The protests were the spontaneous actions of people, mainly young, suffering poverty and oppression under existing regimes. The protestors were initially leaderless, and the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) leadership in Egypt was caught by surprise. At first, they even debated whether they should take part in the demonstrations or not.

Apart from calling for “the fall of regime”, the protestors lacked a clear vision and direction of what should come next. More organised groups like the MB, eventually mobilised their followers and networks, and took up leadership of the protestors.

Even though President Hosni Mubarak was eventually removed from power, the Egyptian military through the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) using the MB reasserted control over the masses and started to negotiate a new constitution and elections. The MB with the army delivered elections working with the old military intelligence and rulers, instead of the revolution that the people were calling for.

The Freedom and Justice Party of Mohamed Morsi linked to the MB won the elections that followed. Morsi became the democratically elected President of Egypt. It was Morsi himself that appointed Abdel Fattah el Sisi as Defence Minister on the 12 August 2012. Effectively making him the commander in chief of the armed forces (he had previously been Director of military intelligence).

In both Tunisia and Egypt, the outcome of the protests, namely democratic elections, led to MB linked parties coming to power, and eventually being subverted out of power. In June 2013, a second wave of mass protests calling for revolution started (sometimes called the second revolution). This time, the target of the protestors was President Morsi and the MB themselves who were seen as betraying the revolution.

Abdel Fattah el Sisi and the military, again intervened to subvert the revolution by removing President Morsi in a coup and launching a crackdown on the MB, and others behind the second revolution, which has lasted till this day. President Morsi was therefore removed by the man he had appointed. Both the military and people that had endorsed the MB had turned against them. The first and second revolutionary movements in Egypt had successfully been countered by the military and old order. A broadly similar outcome over a longer period has been achieved in Tunisia. There has therefore been no revolutions.

Revolutions usually over-throw existing political orders. This only happened in Libya with the aid of Western military powers, but with no leadership or group able to take up leadership or power afterwards. War fuelled by external countries supporting different factions is continuing until now.

In Yemen and Syria, the chance for revolutions looked promising. The existing ruling orders launched violent crackdowns on protestors. However, the opposition in both countries looked as if they would take power. In both Yemen and Syria, the old ruling elites were then saved from collapse and propped up, by external powers intervening in the country.

However, despite much bloodshed, in Libya, Syria, and Yemen the old political systems are effectively broken, and new ones will have to emerge or be created to replace them eventually. So, the prospect for more radical change remains greater in the long term.

A study of the history of revolutions can help us identify those factors that usually define successful revolutions. We can examine the French and European revolutions in the 19th century. Or the Russian (1917) and Iranian (1979) revolutions ; or those that that led to capitalism replacing communism in the Old Soviet bloc countries in Russia and Eastern Europe, much later in the 20th century.

In doing so we find they contained most of the following key factors.

- A clear and opposing political vision and values to that of the existing order.

- That vision is simply argued and conveyed to the masses of people and wins over significant parts of the middle class and elites.

- A clear leader or leadership that represent that opposition and communicate that new vision and values to the people.

- An organisational base or mass movement in support of the new vision and values, that will protest, defend, and fight for the new leadership and vision.

- The surrender or submission of the military that protects the old order and a transfer of authority to the new leadership.

- A group of people dedicated to defending the new guard from the inevitable counter revolution from those that support the old regime.

- A group of people committed to the new vision who will rule and govern in place of the old guard.

- Elections usually come after the revolutions have taken place, not before, and are not themselves a vision or ideology.

It appears the leaders of the Arab Spring, especially those of the Islamic groups, made the same miscalculations that the Algerian Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) had made in 1982. There too a revolutionary movement and moment in history was subverted. The FIS leadership mistook elections for revolution and trusted the old guard and military to deliver change.

In Egypt and Tunisia, the MB in fact successfully delivered what they believed in and wanted, namely democratic elections and party-political victories. They then found that Western governments were not as committed to the democracy that they had been preaching to the Muslim world.

Another fundamental miscalculation was to give the old regime legitimacy and trust it, hoping that it could be reformed. History has shown that is rarely the case. The old guard and interests with external support, will nearly always move to or manufacture a counter – revolution. Successful revolutions have tended to treat the old order as illegitimate and needing to be removed from power.

It is human nature to want to bring about a peaceful transformation, and most revolutionary movements start with that goal. However historically, peaceful radical political change is rarely achieved, because those who do not want to change will resist with violence. In Algeria in 1982 the protestors chanted “our revolution will not be a bloody one, it will be peaceful”. The end outcome was more bloody and violent than many revolutions have been. All the Arab Spring protests started peacefully and wanted peaceful change. Yet the counter revolutions in Egypt, Syria, Libya, Yemen, and response to them has been more violent and led to more bloodshed than many successful revolutions. In Tunisia, violence now appears to be starting.

The Arab Spring protests were therefore not revolutions. They were revolutionary protests and moments, which may well return because the people’s lives have not improved and demands for “the fall of the regime” have not been met. On the other hand, the old orders do not want to change and relinquish power peacefully, so more violence appears inevitable even if not desirable.

In politics, one should not use the word failure but learning (from history), revolutions happen in phases and stages. The Arab Spring was just the start of a political process of change not the end. There is much to learn from history and the Arab Spring and real political change is yet to come.

Leave a Reply