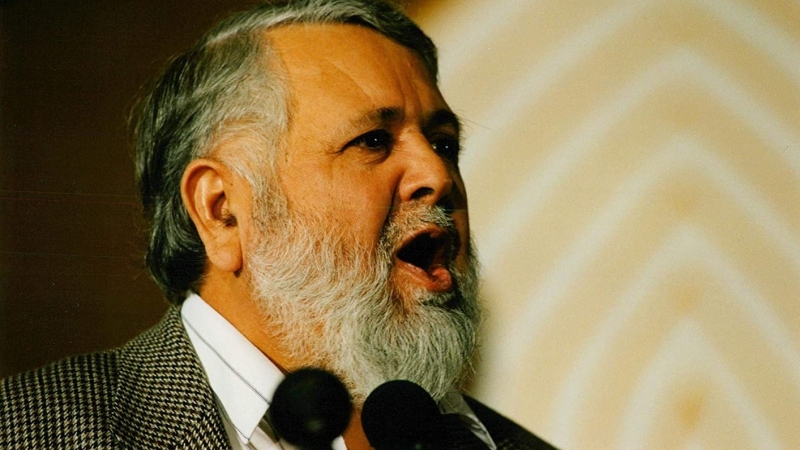

Yahya Birt of the Ayaan Institute recently assessed the core legacy of the late Dr. Kalim Siddiqui which he argues is still relevant for Muslim politics today.

Giving Ourselves Permission – The core legacy of Kalim Siddiqui, the Muslim Institute, and the Muslim Parliament

We Muslims are living through a moment of profound clarity. Our neighbours cheer on or observe a studious silence over the genocide in Gaza. Yet again, Pankaj Mishra’s “bland fanatics” have sharply reminded us that liberalism, equality, human rights, a post-racial multiculturalism, democracy and even some recognition of Islam as Britain’s second religion are not on the table, and never really have been. They are for the West, not for the Rest. We scoffed at the migrant generation who kept their suitcases packed on top of their wardrobes, but we have forgotten the precarity they knew. It is in this moment of clarity that I do not counsel despair. Despair is the attitude that we can do nothing: all we Muslims can do is subsist. But this world is premised upon God, and God is Al-‘Adl, He is the Just. Unless we begin with that, we are with Jonah in the belly of the whale, and must praise God, and realise we have wronged ourselves (Q 21:87‒88).

Today, I want to propose that we revisit and reclaim Kalim Siddiqui (1931‒96) as a radical voice that speaks to our times, to a post-Brexit Powellite Britain now roaring since the postcolonial chickens came home to roost. What indeed are Britain’s four million Muslims to do at this painful juncture? How do we go back to living with people who think we are subhuman? Siddiqui, our underrated desi Malcolm, has something important to teach us.

It is a truism that British Muslims came of age politically during the Rushdie Affair (1988-89), that it was the first time they mobilised qua Muslims in post-war Britain across ethnic and sectarian lines – in this instance, to defend the Prophet’s honour.

The Muslim Institute played a catalytic role in this mobilisation, as it allied itself with the British Pakistani Barelwi pīrs and their followers, the sleeping giants of British Islam, who were the engine of the protests. It was not anger that drove them but their love and devotion to the Prophet summoned up against Rushdie’s calculated satire, whose honour they felt compelled to defend.

The Institute certainly did not seek out a fatwa from Iran, an embedded myth that the BBC still dutifully spread on the thirtieth anniversary of Khomeini’s responsa in 2019. In fact, Kalim Siddiqui’s unpublished diaries, which I have examined, make no mention of the fatwa at all until Iran’s intervention. Of course, thereafter, the Institute became a most effective voice for that deep sense of insult and hurt.

During that period, between 1989 and 1997, British Muslims realised they had to become more nationally coordinated. A number of efforts now forgotten fell by the wayside. Only two live on in the memory. One was the Muslim Council of Britain, established in 1997, which is still with us. It was modelled on the Jewish Board of Deputies, although unlike synagogues most mosques lack formally subscribed memberships, a critical difference that fatally weakened the Council’s representational logic from the beginning in its endeavour to speak to government on behalf of the Muslim community. Having been in the political wilderness on and off for nearly twenty years now, an independently-minded MCB has not been able to fulfil its representational raison d’être. Its future appears uncertain, at least so it seems to me.

Kalim Siddiqui’s alternative, the Muslim Parliament, was short-lived, lasting only six years. It has often been dismissed as too radical, as designed to provoke the British establishment rather than engage them. I would propose that we ditch the received take on the Parliament and look at it again with unjaundiced eyes.

Rereading the Draft Prospectus of the Muslim Institute from 1974 and The Muslim Manifesto of 1990, alongside a speech from that same year, “Generating Power Without Politics”, it is apparent to me that Siddiqui articulated a Muslim version of the Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s. In short, a “Muslim Power” position. Like the Black Power movement, he had no faith that the nation-state or the international order could deliver justice. He looked to the Ummah like they looked to Africa. He navigated minority realities but faced outwards: for him, British Muslims were part of the Ummah in the United Kingdom. His focus was to create robust independent community institutions, and while in 1990 he thought Iran could be an honest sponsor we may more profitably return to the Siddiqui of 1974 who saw Ummatic civilizational renewal as possible without an immediate need for any such sponsor. Indeed, Siddiqui was an early sceptic who did not believe the postcolonial nation-state system could provide any real prospect of Islamic civilizational renewal, even during its honeymoon period before 1967. Looking back fifty years later, his scepticism has aged well; so too has his prescription not to limit our political imagination to British parliamentary processes and the party political system.

He argued that the Muslim minority must through mutual consultation authorize its own independent institutions, both centralized and devolved, to empower its religious, cultural, economic, and political life. The key part here was not patronage but a serious moral and ethical commitment to developing and strengthening the core institutions of the Muslim minority. In essence then, self-authorization is more important than external validation, although experience teaches us that taking steps towards self-authorization are precarious, and are targeted domestically and by various Muslim states and movements.

Kalim Siddiqui articulated two concepts to describe this process of self-authorization by the Muslim minority. The first was “minority political system” by which he meant a structured and institutionalized process whereby Muslims could deliberate and consult with each other to determine their challenges, goals, and priorities. The second was “nonterritorial Islamic state” by which he meant the Muslim minority would authorize and empower an executive function to deliver upon its goals and priorities.

The practical expression of these ideas was the Muslim Parliament. What the Parliament did was to give the Muslim community an ability to think strategically and to create the independent institutions it needed to thrive. Out of the need to regulate the halal meat industry arose the Halal Food Authority, which is still with us today. In ways unimaginable to us now after the War on Terror years (2001‒2021), the Parliament took a leading role in raising awareness and practically supporting the Bosnians in their hour of need, even raising money for arms. Contrast that with our current condition today where we cannot even speak of the right of the Palestinians to defend their homes without falling foul of counter-terrorism legislation. Some of the Parliament’s more short-lived ideas were necessary enough to be reinvented – in this light, one might consider the National Zakat Foundation to be a conceptual descendant of the Parliament’s Bait al-Maal.

So self-authorization to create a viable, independent community was, it seems to me, the chief legacy of the Muslim Parliament. We have tried patronage and it has failed us. It is time to rethink radically how we do politics as Muslim minorities, and it is the Muslim Parliament’s magnificent failure that gives us much food for thought as we ponder life after Gaza.

Leave a Reply