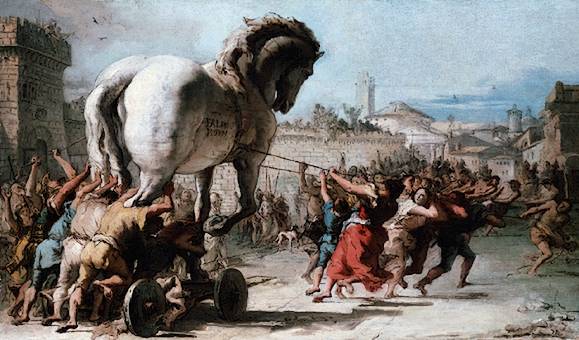

A new podcast produced by Serial Productions and co-hosted by Hamza Syed and Brian Reed has shone a light on the sordid Trojan Horse Affair. At the heart of the affair was an anonymous letter that alleged a secret plot, codenamed Operation Trojan Horse, orchestrated by Muslim professionals to take over and ‘Islamise’ Birmingham’s schools. The letter appears to be a correspondence between two conspirators and was allegedly found by an anonymous source in their manager’s office. Four pages of it were photocopied and sent to the then head of Birmingham City Council, with a cover letter that threatened to leak the letter to national newspapers if its contents were not investigated within 7 days.

The letter was widely considered to be fraudulent, and the chief protagonist of the alleged plot (Tahir Alam) was able to quickly identify who he believed to be the likely author of the letter. An internal audit commissioned by Birmingham City Council at the time the letter was leaked, which became the subject of clandestine meetings between the podcast co-hosts and the former leader of Birmingham City Council, also found that the letter was likely to be fraudulent. But the author of the letter was never formally identified and the two co-hosts of the podcast travel far and wide to try to uncover the author in an attempt to understand why it was written.

Listening to the podcast one is left with a sense of disbelief: how is it possible that a letter widely considered to be fraudulent, which emerged in the context of local discontent in schools, could not only lead to a witch hunt against Muslim school teachers but also foment national hysteria about the presence of Muslims in Britain?

Part of the answer lies in the strategic ignorance (Sullivan and Tuana, 2007) that is deliberately cultivated, in the face of racist outcomes and injuries of events, by those who benefit from them. Strategic ignorance functions to keep the racist lie alive so that it can wreak its havoc. Given that the letter emerged in the context of a ‘war on terror’ in which there were already pre-existing narratives about the threat of Muslims to the west, this wasn’t difficult, and they provided the main frame of reference to make sense of the letter. Indeed, the government itself appointed a former counterterrorism police chief (Peter Clarke) to lead its investigation. Prior to that, Clarke was appointed to the board of the Charity Commission in 2013 when Shawcross was Chair (Shawcross is currently leading the government review of the Prevent strategy), and when it began to heavily target and investigate Muslim groups.

As a result, the national reaction to the alleged plot detailed in the letter was rather predictable and damaging for Muslim communities. Several teachers at schools named in the Trojan Horse letter were banned from the education sector and some former students removed all reference to the named schools from their CVs and job applications for fear of repercussions. In 2014, the government introduced the Counterterrorism and Security Act which made the Prevent strategy a legal duty for public sector institutions. The Trojan Horse Affair provided an easy rationalisation for the legal duty, particularly in schools where the bulk of the Prevent referrals to the Channel programme emanate. Since its inception it has resulted in thousands of young Muslim school children being referred to the Channel programme and created a climate of fear in schools, colleges, and universities. The Prevent Duty also requires schools to promote ‘fundamental British values’ and their compliance on that is monitored by OFSTED. A year later in 2015, the government introduced a counter-extremism strategy which, on the back of the Trojan Horse Affair, created the Extremism Analysis Unit at the Home Office to monitor and compile blacklists of ‘extremist’ individuals and organisations. These powers were introduced to target those individuals and organisations considered unacceptable for engagement but that had not necessarily broken the law. It introduced new powers to ban suspected ‘extremist’ groups and individuals and restrict access to premises used for ‘extremist’ purposes (typically mosques and community centres). The overarching aim of the new powers in the Counter-Extremism strategy were to set in motion a counter-entryism operation across the public sector to hunt down other dangerous Muslims that might be planning or executing Trojan Horse style operations. In other words, both the Prevent Duty and the Counter-Extremism strategy used the sense of suspicion about Muslims that emerged from the Trojan Horse Affair and extended it across the nation by legalising a mass referral system underpinned by the surveillance of Muslims. The damage of the Trojan Horse affair continues to be felt by Muslim school children today who find it increasingly difficult to practice their faith at school.

The weaponization of the Trojan Horse letter was necessary for the legitimacy of the raft of new counterterrorism policies and powers and it functioned as a key piece of evidence in demonstrating the need for the new draconian powers. But a strategic ignorance about the authenticity of the letter had to be cultivated that would allow the government to act as if the letter was indeed evidence of a real plot in order to preserve its image as an ethical actor working for the wellbeing of all in the face of a national threat. It was also necessary to protect the new counterterrorism powers that were ventured on the letter in order to further discipline and control Muslims. The widely known nature of the letter (fraudulent) was made into an unknown to clear the way for new counterterrorism legislation and policy (Zulaika, 2012).

As Sullivan and Tuana (2007) argue, where it concerns racist injury, exploitation, and oppression, ignorance is not necessarily an accidental oversight that can be remedied with new information. Instead, it is a deliberate position that is cultivated for the purposes of domination and the simultaneous projection of innocence. Actively not knowing and not wanting to know go to the heart of strategic ignorance. The power of strategic ignorance is to formally institutionalise what is known and unknown and a lot of energy is expended in maintaining such a status quo so that those that benefit from it, can ardently believe in the lie, and not have to deal with the reality and consequences of it. The costs and benefits of ignorance mean that those ensnared in it have a vested interest in keeping up appearances. The ‘passion for ignorance’ (Zulaika, 2012:57) which sits at the heart of counterterrorism demands that we never see, never listen to, and never talk to extremists and terrorists ‘lest someone might identify with their cause’. Throughout western history strategic ignorance has played a key role in maintaining the image of the west as a benevolent force for good in the world at times when its conduct suggested otherwise. For example, Baldwin (1985) argued that white America could not accept the veracity of the grievances from Black America related to slavery because it would implicate it in racial oppression and destroy its image of itself. Therefore, a strategic ignorance was cultivated to undermine the grievances of Black America. In the ‘war on terror’ the impact of drone strikes, namely, that they have been responsible for the death of thousands of innocent civilians and played a key role in the resentment of the west (Open Society Justice Initiative, 2015; IHRCRC, 2012), is dismissed by denying the civilian death toll by counting all military age males in the vicinity of a drone strike as a ‘militant’ (Greenwald, 2012).

Following the revelations of the Trojan Horse plot a similar concerted effort was made to ignore crucial facts and aspects of the case and there was a refusal to identify the author. First, in investigating the alleged plot, the principle of ignorance determined that both official investigations (by Peter Clarke and Ian Kershaw) did not concern themselves with finding the author of the letter, or determining whether it was a hoax. Instead, they both proceeded as if the alleged plot was real. When both reports were published, the Clarke report found no evidence ‘of terrorism, radicalisation or violent extremism in the schools of concern in Birmingham’ and ‘no evidence to suggest that there is a problem with governance generally’. Similarly, the Kershaw report found ‘no evidence of a conspiracy to promote an anti-British agenda, violent extremism, or radicalisation in schools’ and reported ‘there is little express evidence to which I can point of a systematic plot or co-ordinated plan to take over schools serving students of predominantly Muslim faith or background’. These findings were mirrored in the report by the Education Select Committee on the alleged plot which found ‘no evidence of extremism or radicalisation, apart from a single isolated incident, was found and that there is no evidence of a sustained plot nor of a similar situation pertaining elsewhere in the country.’

Second, the then Education Secretary Michael Gove set aside reservations relayed to him about the plot and pressed ahead with harmful interventions. He was briefed by Birmingham City Council in February 2014 that there was a ‘serious credibility gap’ regarding the letter because it contained ‘serious factual inaccuracies and, in a number of areas, contradictions.’ Gove was also briefed about Birmingham City Council’s own audit report into the allegations which found there was no basis for the allegations and was told of West Midlands Police recommendation that the letter was ‘bogus’.

Third, the then Education Secretary Nicky Morgan was accused of misleading Parliament about the Trojan Horse affair when she presented her department’s report, about which Professor Holmwood said: ‘She knew, or ought to have known, that the report was inaccurate on a number of material points, and misrepresented the situation with regard to Muslims and the schooling of pupils in East Birmingham.’ By doing so, she enabled the strategic ignorance of Parliament on the matter.

Fourth, the podcast details various bits of evidence that were ignored to give credence to the allegations in the letter and question the governance of the named schools: the testimony of handwriting experts who determined that the four teaching assistants at Adderley School did not sign their own names on the resignation letters which preceded the Trojan Horse letter; the misspelling of Shahnaz Bibi’s name (one of the four teaching assistants at Adderley) on a resignation letter that Rizvana Darr (head teacher of Adderley) insisted was written by Shahnaz herself (thereby suggesting she misspelt her own name); and the previous OFSTED reports that praised the schools as ‘outstanding’.

Fifth, there were factual errors in the letter, such as a claim that Noshaba Hussain (former head teacher of Springfield school) was hounded out of her post by the plotters when in fact she left in 1994 (as an interesting aside, Noshaba’s unproven claims about Muslim extremists influencing schools was the template later used at Adderley where Rizvana was head teacher). In fact, there was very little fact checking of the allegations contained in the letter, either by the journalists that initially broke the story for The Times or by the British Humanist Association which received a complaint about Birmingham Schools by two white teachers, because to do so would tug at the veil of ignorance under which the state and sections of the mainstream media were shamelessly residing.

All the above (the evidence and key areas of further investigation) had to be deliberately ignored whilst evidence of the influence of an Islamic ethos at the schools was amplified to protect the narrative of the Trojan Horse plot and everything that had been ventured on it. The strategic ignorance surrounding this alleged plot enabled much of the counterterrorism infrastructure that came after it. The problem posed by this new podcast is not just that it questions the narrative of the alleged Trojan Horse plot and what that means for the Prevent Duty in the education sector and the counter-extremism strategy with its focus on counter-entryism in the public sector, but that it forces those previously residing under the veil of ignorance to confront the consequences of their actions and the damage they caused to Muslim communities across Britain. It is for that reason that in its review of the podcast, the Financial Times critiqued the podcast for its focus on the details, because the detail shatters the illusion. And it is for that reason, that Mark Walters (formerly of Adderley School who supported head teacher Rizvana Darr’s version of events about the resignation letters), who fled Birmingham to the other side of the world, remained cowering in his office in Perth, when confronted by Achmad Da Costa who knew enough about the story to shatter his strategic ignorance. Mark Walters could not deal with the consequences of the events and so he remained in his office whilst Achmad Da Costa stood on the other side of his office wall.

References

- Baldwin, J. (1985) The Price of the Ticket. New York: St. Martin’s Press

- Greenwald, G. (2012) ‘Militants’: media propaganda’, in Salon.com

- International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic (2012) Living Under Drones: death, injury, and trauma to civilians from US drone practices in Pakistan. Stanford Law School

- Open Society Justice Initiative (2015) Death by drone: civilian harm caused by US targeted killings in Yemen. New York: Open Society Foundation.

- Sullivan, S. and Tuana, N. (2007) (eds.) Race and epistemologies of ignorance. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Zulaika, J. (2012) “Drones, Witches and Other Flying Objects: The Force of Fantasy in US Counterterrorism’, in Critical Studies on Terrorism. 5(1): 51–68

Dr Fahid Qurashi Is a Research Director at the Ayaan Institute

Leave a Reply